The first chapter in my book about end-of-the-world movies, Armageddon Films FAQ, deals with ten classic apocalyptic novels that had never been turned into movies. To show why such books have remained landmarks in science fiction and horror, as well as why they keep getting passed over by Hollywood, the chapter takes on the voices of those arguing such points at a studio – with a reader giving details about the book, an agent pushing the project, and a studio bean-counter attempting to find all the reasons to avoid it. As mentioned in the chapter, although passed over, many of the novels had been cannibalized left and right over the years for various other apocalyptic movies, with Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End being a prime example for such usage.

In September 2014, the cable network SyFy Channel announced that they planned to finally take Clarke’s novel out of that list, with a miniseries adaptation to be filmed in 2015. Having Matthew Graham, co-creator of Life on Mars and Ashes to Ashes, on board sounds intriguing (he also wrote the Doctor Who episode “Fear Her” but … well, he created Life on Mars, so let’s not hold it against him). However, the plot-points given by the cable channel seem to play the miniseries up as rather like a variation of V (what appear to be friendly aliens are anything but, and now humanity must fight the same alien race they once welcomed), but let’s hope that this is just shorthand for more than chase-scenes with aliens for six hours.

No doubt, when reviewing the book, the studio – in this case Universal – brought up several of the same issues as seen in this excerpt from Armageddon Films FAQ. As readers will see, my own conclusions are not quite what has come about, but time will tell if I’m closer to be right than they are.

Script Reader’s Analysis: For many years Arthur C. Clarke was considered one of the “Big Three” in Science Fiction, along with Robert Heinlein (Starship Troopers) and Isaac Asimov (pretty much everything else … okay, that’s a rare joke from this reader, but Asimov was prolific as a science author and Science Fiction writer, including I, Robot, which was adapted as a hit movie for Will Smith). Clarke (1917 – 2008) may not have been quite as busy as Asimov, but certainly contributed in abundance to the printed page, with written pieces on scientific advances as well as his short stories, novellas and novels over the years. Best known is his collaboration with Stanley Kubrick on the movie and novel 2001: A Space Odyssey, which was originally pitched between the two as an adaptation of his short story, “The Sentinel,” although there are certainly aspects of Childhood’s End in the finish work as well. Besides 2001, Childhood’s End and “The Sentinel,” Clark created some of the better known short stories and novels in the genre, from Rendezvous with Rama to “The Nine Billion Names of God” (an apocalyptic short story) to The Sands of Mars.

Childhood’s End has been seen as written by Clarke when he still had some aspects of wonder pertaining to the paranormal (beliefs he discarded later in life, although they led to his use of telekinesis as a plot-device in the novel), but namely his early conviction in the wonders of science and how advancements in the field can deem mostly positive instead of negative results. Although aspects of Childhood’s End could be seen as being gloomy, Clarke champions that such treks into the future could be of amazement and for the positive.

The Plot: It is the time of the Cold War’s Space Race between the U.S. and Russia when aliens arrive, offering advancement and peace for all of Humanity. After some hesitation, the people of Earth begin to cooperate with the aliens and peace does come quickly to the world, but at the cost of creative interest in the arts and sciences. Many years later, children are born who exhibit telekinetic abilities that separate them from their parents mentally and, soon after, physically as they relocate to a continent of their own.

Before this occurs, however, the aliens – now known as the Overlords and who are satanic in appearance – find that a human named Jan Rodricks had stowed away on one of their supply ships. He arrives on the Overlords’ home-word and discovers that the aliens are merely servants of a greater power called the Overmind – made up of various alien races that have moved beyond the physical level and joined together as one entity. The Overlords’ task is to find worlds where the inhabitants are close to achieving a new stage of evolution, much as which occurs with the children on Earth, and prepare them to join with the Overmind.

By the time Jan returns to Earth many decades after his departure, the children are namely the only ones left, as most of those that came before them have died or are in the process of dying. The Overlords and Jan observes the final stages of preparation for the children to become part of the Overmind, with Jan staying to report to the Overlords first-hand what occurs as the aliens back off to a safe distance in space. With the startlingly rapture-like departure of the children, Jan feels a wave of fulfillment for the Human Race as they move up on the evolutionary scale, even as he dies and the earth crumbles around him and disappears. With the disappearance of Earth, the Overlords move on to their next assignment.

As noted above, Clarke’s suggestion of aliens coming one day to help propel Mankind into a greater era can readily be found in 2001 with the usage of the Monolith (elements of such alien involvement stopping dead a Cold War can also be seen as a major plot-point in the sequel film and novel, 2010; not to mention used as well in the James Cameron’s The Abyss). However, Kubrick hid that revelation behind a lot of special effects and metaphorical images, intentionally obscuring the meaning in the process. The television series Babylon 5 also used many elements about the Overlords as part of the alien species in the series called the Vorlons; down to the revelation that they are helping Mankind move to a higher evolutionary plane, as well as their physical appearance being biblical in nature (albeit as angels instead of demons). Still, the plot of the film hasn’t really been pushed much in film over the years and once the late topical element of the Cold War is excised the story could stand as-is for a movie. The element of children gaining telekinetic powers soon after the arrival of aliens may be seen as a bit reminiscent of The Midwich Cuckoos (1957 and adapted into film as Village of the Damned in 1957 and 1995), but that book saw such children as pretty much alien invaders, while Clarke’s earlier work saw it as an evolutionary step-up for Mankind. The main thing would be to avoid comparisons, even if our argument would readily be, “Clarke was there first.” In reality, he was there second in many ways, as it is easy to see elements of Stapledon’s Last and First Man in the novel – a work that Clarke readily admits was very influential on him in his early career.

Agent’s Pitch: Once again, another known author’s name is involved with the project we are reviewing, which is always a plus. People know 2001 and the sequel film is a bit of a cult-favorite amongst Sci-Fi fans, so there a safety net right there as to building a picture around one of Clarke’s novels. There is also a lead character, Jan, who is intertwined into the story, so we don’t have the loss of audience identification that comes with some of the other novels – like Last and First Man and A Canticle for Leibowitz where actions take place over centuries and has no consistent character to root for. Okay, admittedly he disappears for the good chunk of the story on Earth as he sails off to the Overlords planet, but at least he comes back and has explained to him what has occurred. Even better, we could build the story around Jan’s adventure solely and we avoid some of the depressing material about parents losing their kids to the “next evolutionary step” and killing themselves in despair (which appears in the novel). Make him the one that discovers what they look like and conflate the time-period things occur so that it can be within Jan’s lifetime and you’ve still got Childhood’s End with a meaty part for a major actor like Will Smith.

Bean-Counter’s Response: I was going to suggest that, much like Stapledon’s book earlier discussed, this may be more to bite off than we can chew. However, the Agent does have a good point that we may be able to move a few things around, make this more about the one character, and still have it drive home the same message as the book. However, let me point out that earlier attempts have been made to get a script into shape for Childhood’s End, with Universal looking into making it into a film in the early 2000s, but nothing came of it. This may be enough of a history to show that, while the intentions may be good, the project just won’t gel. Might be best to avoid.

Studio’s Decision: Have to agree with the Bean-Counter here. There are certainly enough projects out there to complete rather than one that seems to have been batted around for decades with no resolution. A movie about how we’re all insects and the kiddies are going to destroy Earth just because they want to leave home probably would be a hard-sell to the American public. Maybe if the agent can solicit someone to throw together a script that can impress, or actually can get Will Smith to express interest, we’ll take another look at it.

For more insight into nine other famous novels that have never been made into major studio films, as well as reviews of films covering everything from zombies, to contagions, to alien invasions, pick up a copy of Armageddon Films FAQ - available in bookstores and through Amazon, B&N, and other online outlets!

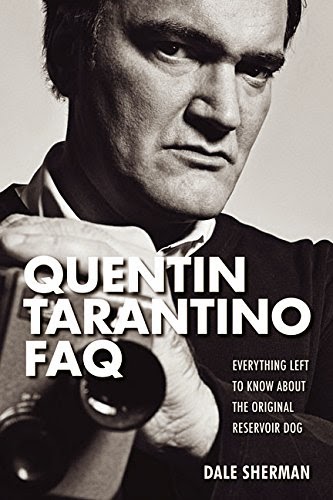

And keep an eye out for Dale's next book, Quentin Tarantino FAQ, available March 11, 2015 from Applause Books!

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.